In the first part of this series I tackled the issue of what to call one of two very different tea processing steps both referred to as “fermentation.” Â In this installment, I’ll discuss what you might call real fermentation.

One type of Chinese tea, called hÄ“i chá (literally “black tea†but usually translated as “dark tea†to avoid confusion) is often described, confusingly, as “post-fermentedâ€. This, again, is a literal translation from the Chinese term hòu fÄxià o and doesn’t make a lick of sense in English. I don’t know much about the history of this term, but this type of tea is actually fermented, so if you’re calling enzymatic browning “fermentationâ€, then I guess you have to call actual fermentation something different? But I’m getting ahead of myself…

What’s going on:

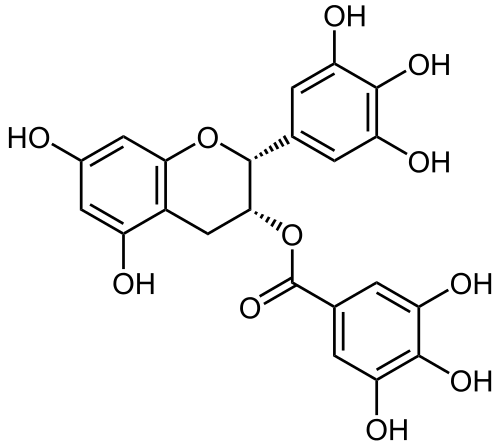

Although there are several kinds of hēi chá, the most popular by far is shu puer tea (also seen—and heard—as “shou†puer). To make this tea, you start by making what is essentially a green tea, and that involves using heat to stop enzymatic browning by inactivating polyphenol oxidase. This dry, loose-leaf green tea is then piled in thick heaps on a factory floor, moistened with water, and covered with a tarp made of natural or synthetic materials. The tea may or may not be purposefully inoculated with microbes either from some bits of the previous batch of tea (a starter culture) or with specific isolated strains of microbes. If it isn’t purposefully inoculated, the microbes involved come from the tea leaves, workers hands, the tarp, the factory floor, or the air (microbes are everywhere!). The microbes doing the work here are mostly fungi, especially Aspergillus niger, a fungus which is also used in the production of soy sauce, and Blastobotrys adeninivorans, but many bacteria are present as well.

This pile of tea quickly heats up from the metabolic activity of the microbes that are multiplying and eating and breaking down compounds in the tea. This heat is important—only very heat tolerant microbes can survive this process, and those happen to be the microbes you want for safety and flavor reasons. It’s also important to keep the pile oxygenated which is done by turning the leaves occasionally—again, this selects for “good†microbes over “bad†ones. Turning and selectively removing the tarp also keeps the pile from getting too hot and killing everything.  During this process, the microbes are not only breaking down compounds in the tea, but they are also producing compounds that otherwise wouldn’t be found in tea. For example, shu puer is often found to contain cholesterol-lowering statins produced by microbes.

After 30 or 40 days, the microbial process is slowed by removing the tarp and piling the tea into furrows to help it cool and dry. The finished product is drastically different from the starting material in appearance, flavor, and aroma.

What to call it:

There is substantial debate over what to call the tea itself in English—the “shu” in shu puer can be translated either as “cooked†or “ripeâ€.  As of late, my strategy is to avoid translating at all and just use the Chinese terms, but after deciding on what to call the process that creates this tea, we might just have some good solid reasoning for choosing one translation over the other.

Compared to the process I discussed in part one, this one is much more clearly deserving of the term “fermentation†because it actually involves microbes. “Post-fermentationâ€, the literal translation of what this process is often called in Chinese, doesn’t make any sense unless you’re going to call some earlier step “fermentation†or if this was something that happened after fermentation. I would personally suggest that “post-fermentation” has no place in any realm of tea discussion and should be totally phased out. Â

So is it that easy? Can we all agree on “fermentationâ€? Well, that’s what I thought until I asked a microbiologist. Ben Wolfe is a microbiologist at Tufts University, and he provided a surprising and insightful comment after learning about shu puer and the microbial players involved in making it.  He asked, “Is this actually fermentation?â€

Just like the term “oxidation†in chemistry, “fermentation†has a slightly different meaning in microbiology compared to everyday English. Fermentation isn’t just any process that microbes carry out—it specifically describes the way microbes get energy from their food when no oxygen is around. Fermenting microbes typically make lactic acid or ethanol as waste products of fermentation. As Professor Wolfe scanned a list of microbes found in shu puer, he noted that none of the most abundant species were typical fermenters.

So what do microbiologists call a food that is made by microbes but not by true fermenting microbes? Ripened foods. Salami, brie cheese, and katsuobushi (AKA bonito flakes) are all examples of microbially ripened foods where exposure to oxygen is necessary in production.¹ On the other hand, kimchi, sauerkraut, and kombucha are all fermented under limited oxygen exposure. Making shu puer is more like making salami than like making sauerkraut because of the importance of oxygen. Too much exposure to oxygen can ruin a batch of sauerkraut but too little oxygen will ruin a batch of shu puer.

If we want to be really specific and geeky, we can call this process microbial ripening which naturally lends support to calling shu puer “ripe†or “ripened†puer in English.

Closing words

Language is crazy complicated, especially so when you’re dealing with two very different languages, industry jargon, AND scientific jargon. I mostly intend this series as a fun, ultra-geeky delve into a few aspects of tea and not as a suggestion for how everyone in the tea world should talk or write. Honestly, introducing yet another set of terms to the tea world probably isn’t worth the confusion even if the terms themselves are less confusing.

My advice is to approach tea terminology with a goal of clear and friendly communication. As long as there is mutual understanding, there’s no need for correction or clarification. There are a few situations where I think clarity is especially important and confusing terms should be avoided. For example, when introducing beginners to the world of tea, “fermentation†is a really confusing term for what is actually “oxidation†or “enzymatic browningâ€â€”I’d avoid that term entirely unless you’re talking about real microbial fermentation or ripening. If you’re writing a scientific publication about tea that a microbiologist or a chemist might read, be clear about whether you mean microbial ripening, fermentation, or enzymatic browning (which all get called “fermentation†regularly). Â

On the other hand, if a tea farmer from China is telling you about how they do the “fermentation†process for their oolong, suppress the desire to interject with “Actually…†and start taking notes instead!

Notes

¹As a side-note, the reactions that ripening or fermenting microbes use to get energy from their food would be characterized as oxidation reactions 😉